Saturday, November 28, 2015

VC, VT, và ST

Sunday, November 22, 2015

Cầu Nguyện và Nguyền Rủa

Another "Story"

Lyrics of Traces by Classics IV, written in 1968, the year she and you started going out came on the radio about half an hour ago. The relationship you had with her lasted only three years, but the impact on you has lasted a lifetime. Love is a strange and yet familiar thing, like Fire. Don't play with Love or Fire. You might get burned and scarred for life.

Faded photographs, covered now with lines and creases

Tickets torn in half, memories in bits and pieces

Traces of love, long ago that didn't work out right

Traces of love

Ribbons from her hair, souvenirs of days together

The ring she used to wear, pages from an old love letter

Traces of love, long ago that didn't work out right

Traces of love, with me tonight

I close my eyes and say a prayer that in her heart

She'll find a trace of love still there, somewhere, oh

Traces of hope in the night that she'll come back and dry

These traces of tears from my eyes, oh yeah

Book Review of "Fortune Smiles"

How IS Defeats Us by Frank Bruni, NYT Columnist

Saturday, November 21, 2015

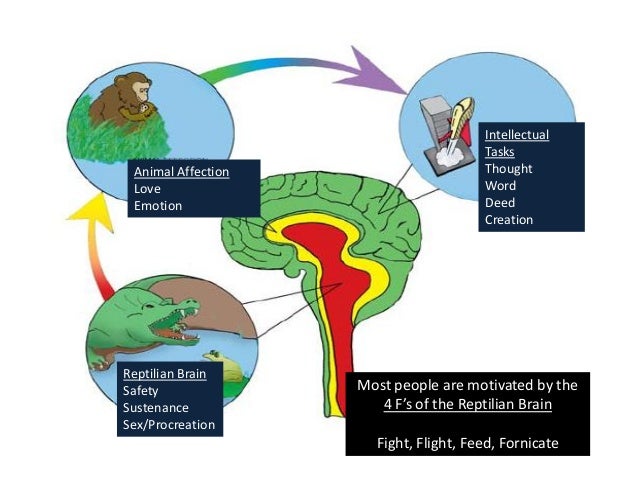

Sự Thật, Não, và Tôn Giáo

Lettre Ouverte à IS

Daechois, Daechoises

Donc ça y est, c’est officiel, vous êtes en guerre contre nous. Ce qui est frustrant, c’est que vous n’avez ni uniforme ni signe distinctif, on ne sait pas vous reconnaître, et nous n’avons donc personne contre qui se battre.

Frustration qui j’espère n’entraînera pas la désignation de faux coupables.

Pourtant même si chaque mort représente sans doute pour vous une victoire, il faut que vous sachiez que vous n’êtes pas prêts de gagner. A dire vrai c’est même impossible.

Parce que quoi que vous fassiez, vous ne nous changerez pas.

Ici, en France, nous ce qu’on aime, c’est la vie. Et tous les plaisirs qui vont avec. Pour nous, entre naître et mourir le plus tard possible, l’idée est principalement de baiser, rire, manger, jouer, baiser, boire, lire, faire la sieste, baiser, discuter, manger, argumenter, peindre, baiser, se promener, jardiner, lire, baiser, offrir, s’engueuler, dormir, regarder des films, se gratter les couilles, péter pour faire rire les copains, mais surtout baiser, et éventuellement se taper une joyeuse petite branlette. On est le pays du plaisir, plus que de la morale. Ici un jour, il y aura peut être une place Monica Lewinsky, et ça nous fera rire. Personne ne l’a jugée, ici.

Alors dans la baise, c’est vrai que nous en France, on fait des trucs avec lesquels vous avez du mal. On aime bien lécher le sexe des femmes. Pas tous, sûrement, mais beaucoup d’entre nous. Et les fesses et le cul, aussi. Là aussi, pas tous, mais bon. Et les femmes aiment bien faire des fellations. On appelle ça des pipes. C’est très agréable. Bien sûr là aussi, toutes les filles n’aiment pas ça, et on ne force personne, mais ça se fait. Régulièrement. Et avec beaucoup de plaisir. Et puis il y a des garçons qui aiment bien ça, aussi. Se faire des fellations ou se lècher ou se pénetrer entre eux. Et les filles pareil. En fait, ici, ce qu’on aime, c’est faire ce qu’on veut. On essaye de pas gêner les autres, c’est le principe, mais on n’aime pas trop qu’on nous dise trop fort ce qu’on doit faire ou ce qu’on ne doit pas faire. Ça s’appelle la Liberté. Retenez bien ce mot, parce qu’au fond, c’est ça que vous n’aimez pas chez nous. Ce n’est ni les Français, ni les caricaturistes, ni les Juifs, ni les clients de café ni les amateurs de rock ou de foot, c’est la Liberté.

La deuxième chose, c’est qu’en tuant comme ça, à l’aveugle, avec un objectif uniquement comptable, vous prenez le risque de tuer des français de plus en plus représentatifs de la France. A la limite en ne tuant que des juifs, ou que des dessinateurs, les non juifs qui ne savent pas dessiner pouvaient toujours vous trouver des excuses ou se sentir étrangers à cette guerre, mais là ça va être de plus en plus dur. Parce qu’en atteignant un échantillon représentatif de la France, vous allez toucher à ce que nous sommes vraiment. Et qui sommes nous, vraiment? Et bien c’est justement ce qui est beau ici, c’est que nous sommes plein de trucs. Bien sûr il y a quelques français français français. Mais il y a des français italiens, des français espagnols, des français arabes, des français polonais, des français chinois, des français rwandais, des français sénégalais, des français algériens, berbères, ukrainiens, géorgiens, américains, belges, portugais, tunisiens, marocains, tchétchènes, ivoiriens, maliens, syriens, des français catholiques, des français juifs, des français musulmans, des français taoïstes, des français bouddhistes, des français athées, des français agnostiques, des français anticléricaux, des français de gauche, des français de droite, des français du centre, des français abstentionnistes, des français d’extreme gauche, d’extrême droite, il y a même sans doute des français djihadistes et même des français futurs terroristes que vous risquez de tuer. Il y a des français riches, des français pauvres, des français sympas, des français gros cons, des français amoureux, des français égoïstes, des français misanthropes. La liste pourrait s’étendre presque à l’infini, avec toutes les combinaisons et tous les sous groupes possibes. Il y a même des français non français, parce que la France étant si belle, il y a toujours et constamment une partie de notre population qui est les touristes. Sans compter les clandestins, qui ne sont peut être pas officiellement français, mais quand même ils vivent là, donc vous pouvez les tuer comme tout le monde.

Ça ça s’appelle l’égalité. Face à la mort, vous pouvez toujours cibler ce que vous voulez, vous nous toucherez tous. Et on va comprendre, nous, ce à quoi vous vous attaquez. Nos valeurs. Simples. Celles qui font que la vie ici ressemble à ce qu’elle est. Imparfaite certes, avec son lot d’injustices c’est vrai, mais ce sont ces valeurs qui font que nous vivons dici de manière aussi digne que possible. Ce pays dans lequel nos pères, et les pères de nos pères et leurs pères avant eux ont choisi de vivre, et pour lequel beaucoup d’entre eux se sont battus.

Et ce qui va arriver, à un moment ou un autre, c’est que nous allons être solidaires, grâce à vous. Nous allons comprendre que ces valeurs sont en danger. Et nous allons les aimer et les faire vivre encore plus fort. Ensemble. Ça ça s’appelle la fraternité.

C’est pour ça que vous ne pourrez pas gagner. Vous allez faire des morts, oui. Mais aux yeux de l’Histoire, vous ne serez que les symptomes abjects d’une idéologie malade.

Bien sûr nous ne gagnerons pas non plus. Des gens vont mourir, pour rien. D’autres vont décider de s’en remettre à des Le Pen, des Assad ou des Poutine pour se débarasser de vous, et nous allons peut être doublement perdre.

Mais vous ne gagnerez pas.

Et ceux qui resteront continueront de baiser, de boire, de dîner ensemble, de se souvenir de ceux qui seront morts, et de baiser.

Sweeping Leaves (new and improved version)

Also read Atheism in Wikipedia where you will learn Atheism also existed in Ancient India

Thursday, November 19, 2015

Envy and Reality

Wednesday, November 18, 2015

Is Any Place Safe?

Paris: The War ISIS Wants Scott Atran and Nafees Hamid from NYR Daily

The shock produced by the multiple coordinated attacks in Paris on Friday—the scenes of indiscriminate bloodshed and terror on the streets, the outrage against Islamic extremism among the public, French President Francois Holland’s vow to be “merciless” in the fight against the “barbarians of the Islamic State”—is, unfortunately, precisely what ISIS intended. For the greater the hostility toward Muslims in Europe and the deeper the West becomes involved in military action in the Middle East, the closer ISIS comes to its goal of creating and managing chaos.

This is a strategy that has enabled it to confound far superior international forces, while enhancing its legitimacy in the eyes of its followers. The complexity of the French plot also suggests how successful ISIS has been at cultivating sources of support within the native populations of secular Western countries. Attacking ISIS in Syria will not contain this global movement, which now includes more than two thousand French citizens.

As our own research has shown—in interviews with youth in Paris, London, and Barcelona, as well as with captured ISIS fighters in Iraq and Jabhat an-Nusra (al-Qaeda) fighters from Syria—simply treating the Islamic State as a form of “terrorism” or “violent extremism” masks the menace. Dismissing the group as “nihilistic” reflects a dangerous avoidance of trying to comprehend, and deal with, its profoundly alluring mission to change and save the world. What many in the international community regard as acts of senseless, horrific violence are to ISIS’s followers part of an exalted campaign of purification through sacrificial killing and self-immolation. This is the purposeful violence that Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the Islamic State’s self-anointed Caliph, has called “the volcanoes of Jihad”—creating an international jihadi archipelago that will eventually unite to destroy the present world to create a new-old world of universal justice and peace under the Prophet’s banner.

Indeed, ISIS’s theatrical brutality—whether in the Middle East or now in Europe—is part of a conscious plan designed to instill among believers a sense of meaning that is sacred and sublime, while scaring the hell out of fence-sitters and enemies. This strategy was outlined in the 2004 manifesto Idarat at Tawahoush(The Management of Savagery), a tract written for ISIS’s precursor, the Iraqi branch of al-Qaeda; tawahoush comes from wahsh or “beast,” so an animal-like state. Here are some of its main axioms:

Diversify and widen the vexation strikes against the Crusader-Zionist enemy in every place in the Islamic world, and even outside of it if possible, so as to disperse the efforts of the alliance of the enemy and thus drain it to the greatest extent possible.

To be effective, attacks should be launched against soft targets that cannot possibly be defended to any appreciable degree, leading to a debilitating security state:

If a tourist resort that the Crusaders patronize…is hit, all of the tourist resorts in all of the states of the world will have to be secured by the work of additional forces, which are double the ordinary amount, and a huge increase in spending.

Crucially, these tactics are also designed to appeal to disaffected young who tend to rebel against authority, are eager for for self-sacrifice, and are filled with energy and idealism that calls for “moderation” (wasatiyyah) only seek to suppress. The aim is

to motivate crowds drawn from the masses to fly to the regions which we manage, particularly the youth… [For] the youth of the nation are closer to the innate nature [of humans] on account of the rebelliousness within them.

Finally, these violent attacks should be used to draw the West as deeply and actively as possible into military conflict:

Work to expose the weakness of America’s centralized power by pushing it to abandon the media psychological war and war by proxy until it fights directly.

Eleven years later, ISIS is using this approach against America’s most important allies in Europe. For ISIS, causing chaos in France has special impetus. The first major military push by the Islamic State Caliphate in the summer of 2014 was to obliterate the international border between Syria and Iraq—a symbol of the arbitrary division of the Arab and Muslim world imposed by France and Great Britain after the defeat of the Ottoman Empire, seat of the last Muslim Caliphate. And because the lights of Paris epitomize cultural secularism for the world and thus “ignorance of divine guidance” (jahiliyyah), they must be extinguished until rekindled by God’s divine radiance (an-Noor).

The fact that the EU’s replacement rate is 1.59 children per couple and the continent needs substantial levels of immigration to maintain a productive workforce—at a time where there is a refugee crisis and amid greater hostility to immigrants than ever—is another form of chaos the Islamic State is well-positioned to exploit. French authorities have found the passport, possibly doctored, of one Syrian national associated with the Paris attacks, as well as two fake Turkish passports, indicating that ISIS is taking advantage of Europe’s refugee crisis, and encouraging hostility and suspicion toward those legitimately seeking refuge in order to further drive a wedge between Muslims and European non-Muslims.

Today, France has one of the largest Muslim minorities in Europe. French Muslims are also predominantly a social underclass, a legacy of France’s colonial past and indifference to its aftermath. For example, although just 7 to 8 percent of France’s population is Muslim, as much as 70 percent of the prison population is Muslim, a situation that has left a very large number of young French Muslims vulnerable to absorbing radical ideas in prison and out. Within this social landscape, ISIS finds success. France has contributed more foreign fighters to ISIS than any other Western country.

One attacker at the Bataclan concert hall, where the highest number of people were killed, was twenty-nine-year-old Ismaël Omar Mostefaï, a French citizen of Algerian and Portuguese origin from the Paris area. He had a criminal record and had traveled to Syria for a few months between 2013 and 2014—a profile similar to the two Kouachi brothers, also French nationals of Algerian origin living in Paris proper, who had trained with al-Qaeda’s affiliate in Yemen before carrying out the Charlie Hebdo attacks in Paris in January.

Other presumed plotters of Friday’s attacks include two brothers, Salah Abdeslam Salah, twenty-six, who remains at large, and his brother Ibrahim, thirty-one, who detonated a suicide bomb near the Stade de France soccer stadium. Although French citizens, the Abdeslam brothers had been living in Molenbeek, a poor Brussels barrio populated by Arab immigrants. In the last year, weapons from that neighborhood have been linked to Parisian-born Amedy Coulilaby, a thirty-three-year-old of Malian descent who had been a jail buddy of one of the Kouachi brothers and who carried out the lethal January attack on a Kosher supermarket in Paris; and Mehdi Nemmouche, twenty-nine, a French national of Algerian origin who spent a over a year with ISIS in Syria and was responsible for the deadly shootings at the Jewish Museum of Belgium. Another of the Paris suicide bombers, twenty-year-old Bilal Hadfi, was also a French national who fought with the Islamic State before returning to Belgium, which has the highest per capita rate of jihadi volunteers from Europe. Two other Belgians, one of whom was eighteen, were also involved in the Paris attacks, as well as a twenty-seven-year-old Egyptian, Yousef Salahel.

As with the 2004 Madrid train bombings and the 2005 London Underground bombings, what seems to be emerging from the fragmentary reports so far is that the Paris attacks were carried out by a loose network of family, friends, and fellow travelers who may have each followed their own, somewhat independent paths to radical Islam before joining up with ISIS. But their closely coordinated actions at multiple sites in Paris indicate a significant degree of training, collective planning, and command and control by the Islamic State (including via encrypted messages), under the likely direction of Abdelhamid Abaooud, known as Abu Omar, “The Belgian,” a twenty-seven-year-old of Moroccan origin from Molenbeek, a former jail mate of Salah Abdelslam, who is known to have traveled back and forth between Europe and the Middle East.

Such coordination has been facilitated by the very large contingent of French foreign fighters in Syria. In April, French Senator Jean-Pierre Suer said that 1,430 men and women from France had made their way to Iraq and Syria, up from just twenty as of 2012. About 20 percent of these people are converts. The latest report from West Point’s Center for Combating Terrorism, which has detailed records on 182 French fighters, notes that most are in their twenties. About 25 percent come from the Paris area, with the rest scattered over smaller regions throughout France. According to France’s Interior Ministry, 571 French citizens or residents are presently in Syria and Iraq, some with al-Qaeda affiliate Jabhat an-Nusra, but most with ISIS. More than 260 people are known to have returned to France, and more than 2,000 people from France have been directly implicated in the jihadi pipeline to and from the region, which extends across Europe: police have already made arrests in Belgium and Germany related to the Paris attacks, and traced the entry into Europe of one of the attackers, a Syrian national, through Greece.

French counterterrorism surveillance data (FSPRT) has identified 11,400 radical Islamists, 25 percent of whom are women and 16 percent minors—among the minors, females are in a majority. Legal proceedings are now underway against 646 people suspected of involvement in terrorist activity. French Prime Minister Manuel Valls conceded after Friday’s attacks that even keeping full track of those suspected of being prone to violent acts is practically impossible: around-the-clock surveillance of a single individual requires ten to twenty security agents, of which there are only 6,500 for all of France.

Nor is it a matter of controlling the flow of people into France. France’s Center for the Prevention of Sectarian Drift Related to Islam (CPDSI) estimates that 90 percent of French citizens who have radical Islamist beliefs have French grandparents and 80 percent come from non-religious families. In fact, most Europeans who are drawn into jihad are “born again” into radical religion by their social peers. In France, and in Europe more generally, more than three of every four recruits join the Islamic State together with friends, while only one in five do so with family members and very few through direct recruitment by strangers. Many of these young people identify with neither the country their parents come from nor the country in which they live. Other identities are weak and non-motivating. One woman in the Paris suburb of Clichy-sous-Bois described her conversion as being like that of a transgender person who opts out of the gender assigned at birth: “I was like a Muslim trapped in a Christian body,” she said. She believed she was only able to live fully as a Muslim with dignity in the Islamic State.

For others who have struggled to find meaning in their lives, ISIS is a thrilling cause and call to action that promises glory and esteem in the eyes of friends, and through friends, eternal respect and remembrance in the wider world that many of them will never live to enjoy. A July 2014 poll by ICM Research suggested that more than one in four French youth of all creeds between the ages of eighteen and twenty-four have a favorable or very favorable opinion of ISIS. Even if these estimates are high, in our own interviews with young people in the vast and soulless housing projects of the Paris banlieues we found surprisingly wide tolerance or support for ISIS among young people who want to be rebels with a cause—who want, as they see it, to defend the oppressed.

Yet the desire these young people in France express is not to be a “devout Muslim” but to become a mujahid(“holy warrior”): to take the radical step, immediately satisfying and life-changing, to obtain meaning through self-sacrifice. Although feelings of marginalization and outrage may build over a long time, the transition from struggling identity to mujahid is often fast and furious. The death of six of the eight Paris attackers by suicide bombs and one in a hail of police bullets testifies to the sincerity of this commitment, as do the hundreds of French volunteer deaths in Syria and Iraq.

As one twenty-four-year-old who joined Jabhat an-Nusra in Syria told us:

They [Western society] teach us to work hard to buy a nice car and nice clothes but that isn’t happiness. I was a third-class human because I wasn’t integrated into a corrupted system. But I didn’t want to be a street gangster. So, I and my friends simply decided to go around and invite people to join Islam. The other Muslim groups in the city just talk. They think a true Muslim state will just rain from heaven on them without fighting and striving hard on the path of Allah.

French converts from families of Christian origin are often the most vociferous defenders of the Islamic State. There’s something about joining someone else’s fight that makes one fierce. When we asked a former body builder from Epinay-sur-Seine, a northern suburb of Paris, why he converted to Islam he said that he had been in and out of jail, constantly getting into trouble. “I was a mess, with nothing to me, until the idea of following the mujahid’s way gave me rules to live by”: to channel his energy into jihad and defend his Muslim brethren under attack from infidels in France and everywhere, “from Palestine to Burma.”

Because many foreign volunteers are marginal in their host countries, a pervasive belief among Western governments and NGOs is that offering would-be enlistees jobs or spouses or access to education could reduce violence and counter the Caliphate’s pull. But a still unpublished report by the World Bank shows no reliable relationship between increasing employment and reducing violence, suggesting that people with such opportunities are just as likely to be susceptible to jihadism. When I asked one World Bank representative why this was not published, he responded, “Our clients [that is, governments] wouldn’t like it because they’ve got too much invested in the idea.”

As research has shown with those who joined al-Qaeda, prior marriage does not seem to be a deterrent to those now volunteering for ISIS; and among the senior ranks of such groups, there are many who have had access to considerable education—especially in scientific fields such as engineering and medicine that require great discipline and a willingness to delay gratification. If people are ready to sacrifice their lives, then it is not likely that offers of greater material advantages will stop them. (In fact, our research shows that material incentives, or disincentives, often backfire and increasecommitment by devoted actors).

In its feckless “Think Again Turn Away” social media program, the US State Department has tried to dissuade youth with mostly negative anonymous messaging. “So DAESH wants to build a future, well is beheading a future you want, or someone controlling details of your diet and dress?” Can anyone not know that already? Does it really matter to those drawn to the cause despite, or even because of, such things? As one teenage girl from a Chicago suburb retorted to FBI agents who stopped her from flying to Syria: “Well, what about the barrel bombings that kill thousands? Maybe if the beheading helps to stop that.” And for some, strict obedience provides freedom from uncertainty about what a good person is to do.

By contrast, the Islamic State may spend hundreds of hours trying to enlist single individuals and groups of friends, empathizing instead of lecturing, to learn how to turn their personal frustrations and grievances into a universal theme of persecution against all Muslims, and thus translate anger and frustrated aspiration into moral outrage. From Syria, a young woman messages another:

I know how hard it is to leave behind the mother and father you love, and not tell them until you are here, that you will always love them but that you were put on this earth to do more than be with or honor your parents. I know this will probably be the hardest thing you may ever have to do, but let me help you explain it to yourself and to them.

And any serious engagement must be attuned to individuals and their networks, not to mass marketing of repetitive messages. Young people empathize with each other; they generally don’t lecture at one another. There are nearly fifty thousand Twitter accounts supporting ISIS, with an average of some one thousand followers each.

In Amman last month, a former imam from the Islamic State told us:

The young who came to us were not to be lectured at like witless children; they are for the most part understanding and compassionate, but misguided. We have to give them a better message, but a positive one to compete. Otherwise, they will be lost to Daesh.

Some officials speaking for Western governments at the East Asia summit in Singapore last April argued that the Caliphate is traditional power politics masquerading as mythology. Research on those drawn to the cause show that this is a dangerous misconception. The Caliphate has re-emerged as a seductive mobilizing cause in the minds of many Muslims, from the Levant to Western Europe. As one imam in Barcelona involved in interfaith dialogue with Christians and Jews told us: “I am against the violence of al-Qaeda and ISIS, but they have put our predicament in Europe and elsewhere on the map. Before, we were just ignored. And the Caliphate…. We dream of it like the Jews long dreamed of Zion. Maybe it can be a federation, like the European Union, of Muslim peoples. The Caliphate is here, in our hearts, even if we don’t know what real form it will finally take.”

France, the United States, and our allies may opt for force of arms, with all of the unforeseen and unintended consequences that are likely to result from all-out war. But even if ISIS is destroyed, its message could still captivate many in coming generations. Until we recognize the passions this message is capable of stirring up among disaffected youth around the world, we risk strengthening them and contributing to the chaos that ISIS cherishes.