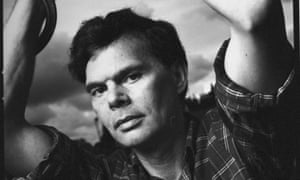

Thom Jones: the writer who explored madness, art and violence

The writer, who died this week aged 71, began his career late in his tumultuous life, exploding onto the literary scene with his Vietnam story The Pugilist at Rest

Thom Jones, the Illinois-born short-story writer who has died, aged 71, of complications from diabetes, rocketed onto the literary scene in 1991, when the New Yorker published his Vietnam War story The Pugilist at Rest. But Jones was no wunderkind: he was in his mid-40s when fame arrived, and had already lived a tumultuous and fascinatingly varied life.

Jones’s father – a schizophrenic who killed himself – was a boxer, and arranged lessons for Jones from a young age. When Jones enlisted as a Force Recon Marine in the 1960s, it was a boxing match that prevented him from shipping out to Vietnam with the rest of his platoon, all but one of whom would be killed in action. Instead Jones, badly beaten by a fellow soldier, was discharged from the army with temporal lobe epilepsy – the same type of epilepsy it is believed that Dostoevsky suffered from.

A civilian again, Jones enrolled in college, and in the early 1970s took the MFA in creative writing at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. He didn’t walk straight into a book deal like some of his classmates, however. Instead he became an advertising copywriter, and later a janitor. During the 11 years he was janitor he claims to have read “roughly” 10,000 books. This was “reading that had to be done”, he told an interviewer in 1998, “and most people working at professional jobs just don’t have that kind of leisure”. During this period, and up until the mid-1980s, Jones struggled with alcoholism. He developed diabetes, and also suffered from depression. He remained on a lot of medication for the rest of his life, one of numerous biographical facts reflected in his fictional characters, who are among the most frequent pill poppers in literature.

Overcoming his alcohol addiction seemed to be the biggest factor in Jones being able to produce the stories he wrote in the early 1990s. “For me it was easy,” he said, perhaps disingenuously: “Produce a text that was so good, an editor could not reject it”. There is another parallel here with Dostoevsky, often referred to in Jones’s stories. When he was writing The Idiot, a novel whose protagonist, Prince Myshkin, experiences several temporal lobe-type seizures, he explained to a friend why he had abandoned a first draft: “I said to hell with it all. I assure you that the novel could have been satisfactory, but I got incredibly fed up with it precisely because of the fact that it was satisfactory and not absolutely good”.

Just how “easy” it was for Jones is debatable, but The Pugilist at Rest was undeniably too good to be rejected. A first-person account of a marine who becomes the sole survivor of an ambush in the Vietnamese DMZ, the story, as with many of Jones’s stories, powerfully conflates autobiography and fiction, and weaves hypnotically between dramatic scenes and essayistic digressions. Jones uses the image of the Roman statue The Pugilist at Rest, based on an earlier Greek original, as a way in to discussing the marriage of violence and art. He wonders if the statue depicts Theogenes, the greatest boxer in antiquity:

The sort of boxing Theogenes practiced was not like modern-day boxing with those kindergarten Queensberry Rules. The two contestants were not permitted the freedom of a ring. Instead, they were strapped to flat stones, facing each other nose-to-nose. When the signal was given, they would begin hammering each other with fists encased in heavy leather thongs. It was a fight to the death. Fourteen hundred and twenty-five times Theogenes was strapped to the stone and fourteen hundred and twenty-five times he emerged a victor.

The narrator tells us that Theogenes fought at “the approximate time of Homer, the greatest poet who ever lived. Then, as now, violence, suffering, and the cheapness of life were the rule”. The narrator himself embodies this divide between culture and violence. He quotes Schopenhauer and Dostoevsky, but he also viciously attacks a fellow trainee marine, and later describes the “reservoir of malice, poison, and vicious sadism in my soul” that “poured forth freely in the jungles and rice paddies of Vietnam”.

The central relationship in The Pugilist at Rest, between the narrator and his buddy Jorgesen, is often repeated in Jones’s work. It’s there in the relationship between the young narrator and the boxing trainer and surrogate father Frank Coles in As of July 6, I Am Responsible for No Debts Other Than My Own, and between the boxer Prestone and his alcoholic trainer Moore in Rocket Man, Jones’s favourite of his own stories. But these man-to-man relationships were not the only ones Jones was interested in. I Want to Live!, selected by John Updike for his Best American Stories of the Century anthology, is a monologue by a woman dying of cancer. A Midnight Clear, one of the pieces Jones described as his “nuthouse stories”, describes a woman and her stepson going to visit a schizophrenic cousin in the state hospital. 40, Still at Home presents an aging, hypochondriac son tormenting his genuinely sick mother.

Jones’s legacy, however, will be defined by his Vietnam stories, uncannily authentic-seeming explorations of a reality that he was bound for but never actually experienced. That fact gives an obsessional, guilt-ridden sense to his constant returns to these same characters who, like the soldiers of Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried, pass from story to story, a bit part player in one becoming the lead in another.

At the end of The Pugilist at Rest the narrator expresses a sense of guilt that he has taken the credit for killing North Vietnamese soldiers that his dead friend Jorgesen killed. “When I think back on it”, he writes, “my tale probably did not sound as credible as I thought it had at the time. I was only 19 years old and not all that practiced a liar”. Are these solely the words of Jones’s narrator, or do they speak to the misgivings of a writer who was often mistakenly described by reviewers as a Vietnam veteran? A fascinating obsession appears to lie at the heart of Jones’s fiction, one that generated some of the most visceral acts of imagination of the last 25 years.

No comments:

Post a Comment