Friday, October 28, 2016

Another, blockbuster from Sweden, as reported in the NYT, A Man called Ove

Conservative Intellectual Crisis by David Brooks of the NYT 10/28/2016

Consciousness in the Universe

Thursday, October 27, 2016

MM

Vietnam's Military Modernization

In the past 10 years, there has been a fundamental shift in the capabilities of the Vietnam People’s Army (VPA), which for the first time has the ability to project power and defend maritime interests. No country in Southeast Asia has put more military hardware online in the same period of time as Vietnam. This military modernization has been driven almost exclusively by the threat posed by China over territory in the contested South China Sea.

What we are seeing now is Vietnam entering a period of consolidation and gradually improved capability, and the gradual development of doctrine. Vietnam has many of the assets in place, but so far, no doctrine in a real sense (beyond “people’s war”) or any sense of cross-service jointness. The groundwork is laid for further military development.

Budget

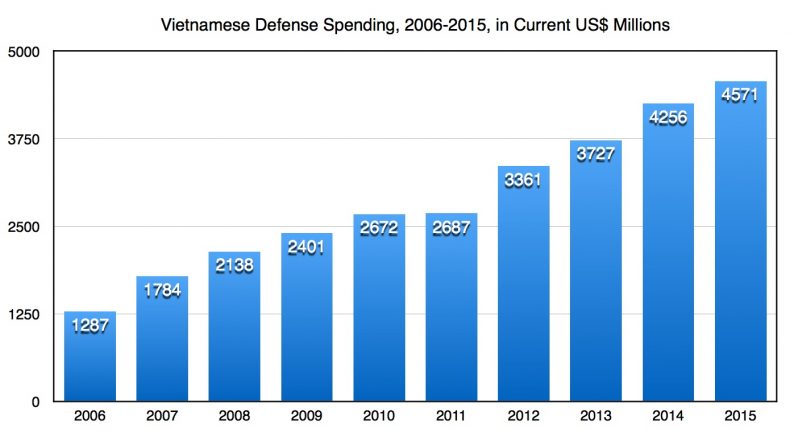

Enjoying this article? Click here to subscribe for full access. Just $5 a month.Vietnam’s publicly released defense budget (its official budget is a state secret) has grown from $1.3 billion in 2006 to $4.6 billion in 2015, a 258 percent increase. In local currency, the budget increased from VND 20.5 trillion in 2006 to nearly VND 100 trillion in 2015, a 381 percent increase, but reflective of the dong’s decline in value. In 2015, according to SIPRI, Vietnam’s defense expenditures were the fourth largest in Southeast Asia, behind only Singapore, Indonesia, and Thailand; all wealthier or significantly larger economies. It was the first year that Vietnam’s spending surpassed Malaysia’s. The defense budget is an estimated $5 billion in 2016, and it is expected to grow to $6 billion by 2020. This, however, is clearly an underestimation and does not include portions of the budget for R&D that may be in other ministerial lines, or from revenue generated from defense-owned industries, especially VietTel, the largest internet and cell phone provider in the country.

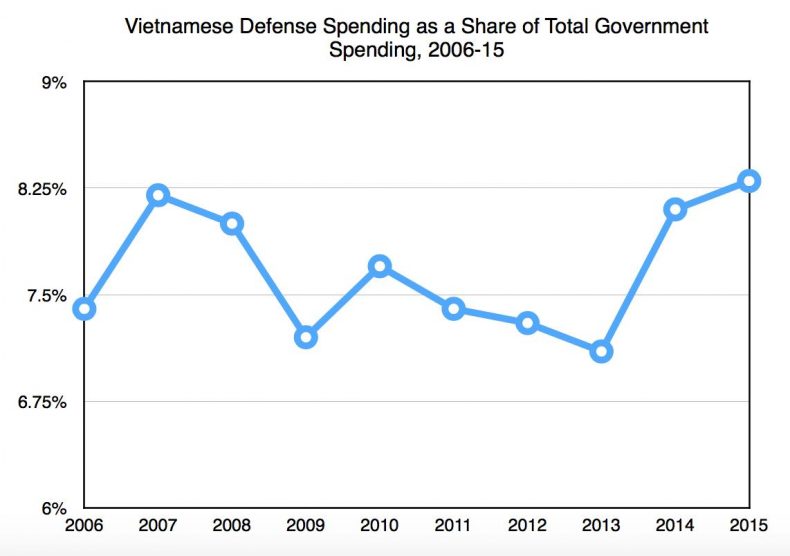

In terms of share of government spending in 2015, Vietnam’s defense spending was 8.3 percent, the third highest share in ASEAN after Singapore (16 percent) and Myanmar (13.3 percent), though just below the ASEAN average. Its lowest rate of spending in the decade from 2006-2015 was in 2013 at only 7.1 percent of government spending. Over the decade, it has averaged 7.67 percent.

Yet, on a per capita basis, Vietnam’s defense spending is quite modest. In 2015, per capita expenditure was only $49 per person, well below the ASEAN average of $388 per person. Even if you removed Singapore, which skews the data, Vietnam still falls well short of the average of $200 per person. Vietnam’s per capita defense spending is the fifth highest in ASEAN, but only above poorer countries: the Philippines, Indonesia, Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia. Nonetheless, between 2006-2015, Vietnam saw a 300 percent increase in per capita spending.

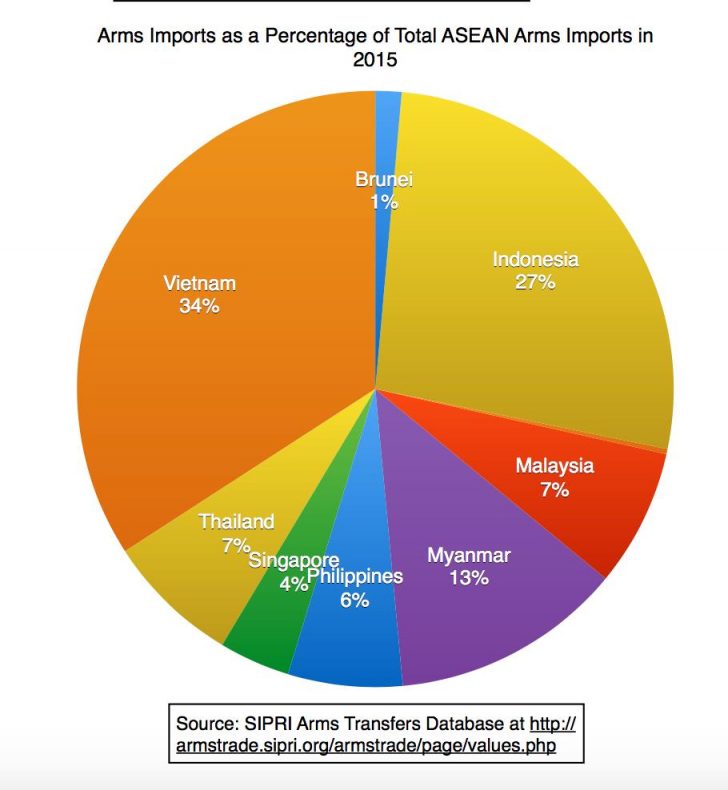

In the period of 2011 to 2015, Vietnam was the 8th largest importer of weaponry in the world, a 699 percent increase from 2006-2010, when it was the 43rd largest. Vietnam accounted for over a third of total ASEAN arms imports in 2015.

Although the leadership is committed to rapidly modernizing its military, defense spending has been prudent and linked to economic performance. Defense spending was only 2.3 percent of GDP in 2015, slightly ahead of inflation. This figure has been very constant over the past decade. There have been very steady budget increases on an annual basis, but still a similar percent of GDP persists, and the budget is tied to Vietnam’s fast growing economy, which has made the VPA a key stakeholder in Vietnam’s economic development.

Defense White Paper

Vietnam’s last white paper was released in 2009, their third. The VPA was reportedly drafting a new version in mid-2015, but suspended the process until after the quinquennial congress of the Vietnam Communist Party (VCP) in January 2016. It was expected that the new leadership would add their imprimatur to the document and that it would be released in mid 2016; but as of the time of writing, there is no discussion of it in the official media. This is most likely due to the fact that VCP General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong was re-elected in January 2016, but was expected to remain in his post for only a half term. As such, political jockeying is already underway, including some high level purges, trials, and crackdowns on dissent.

There are several other reasons to explain the delay. The first is the July 2016 ruling by the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) on the suit filed by the Philippines challenging China’s territorial claims and nine-dash line in the South China Sea. Though the PCA’s ruling in most ways benefits Vietnam more than any other country, Hanoi has been silent on the ruling, and has still not released a formal response. Hanoi is clearly alarmed at the inconsistent statements and policies of Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, who has sought to distance the Philippines from its traditional ally the United States, and who has pledged to not press China with the PCA ruling, instead calling it a “piece of paper with four corners” and accepting China’s historical rights to the waters.

Second, despite the newly acquired defense platforms, it is evident that Vietnam still has not developed doctrines that reflect these newly acquired capabilities. Doctrine has not even begun to keep pace with acquisition. As such, Vietnam has a patchwork of capabilities, without any integrated or joint defense doctrine. That being said, there have been several joint exercises among the branches in the last few years, such as a combined arms exercisebetween the air force, armored units, and infantry in 2014, or an undated recent joint marine-air force amphibious landing exercise, which involved amphibious armored vehicles attacking from tank landing ships (LSTs) and marines descending from Vietnam People’s Army Air Force (VPAAF) helicopters. Thus, jointness is increasingly emphasized in the VPA, but a full doctrine has yet to be announced or seen. More importantly, the air force and navy are not independent services, and at the end of they day they are commanded by army generals. There are no signs that this is going to change any time soon.

Third, Vietnam has been repeatedly caught flat-footed in responding to China’s multilayered operations in the South China Sea, including operations of the People’s Liberation Army Navy, People’s Liberation Army Air Force, Chinese Coast Guard, and its increasingly networked maritime militia. While Vietnam has built one of the largest coast guard forces in the region (much bigger than those of the Philippines, Indonesia, or Malaysia), it has been unable to stop China’s construction of artificial islands and fishing in the disputed region. While the Vietnamese are aware that this is happening, their existing military doctrine remains too rigid, unable to respond in kind, or incapable of utilizing assets in creative and effective ways.

Navy

No service has benefitted more from modernization than the Vietnam People’s Army Navy (VPAN). Vietnam has acquired six Russian-built Kilo-class submarines, five of which have been delivered, and the sixth will arrive in early 2017. That gives Vietnam the most advanced submarine fleet in the region. Vietnam has already trained nine of 12 submarine crews and at least one submarine is currently patrolling without its Russian trainers and advisers. Vietnam surprised many when it successfully purchased submarine-launched Klub anti-shore missiles from Russia. Yet most evidence, to date, is that the ships are spending most of their training time on the surface, with only occasional dives, rather than prolonged underwater training missions.

Vietnam acquired two Gepard-class frigates in 2011, its largest and most modern surface warfare ships. Two more are currently under construction, to be delivered late 2016 or early 2017; these will be equipped with advanced anti-submarine warfare capabilities. A third pair is currently being negotiated.

Vietnam acquired two fast Molniya missile attack crafts from Russia. More importantly, it purchased the production license for six more that have already been built, and is currently negotiating the license to build four more. The new Molniya-class will have additional capabilities, including being armed with Klub ship-to-shore missiles, in addition to the existing Uran anti-ship missile. These will give Vietnam the ability to target any facilities China has constructed in the Spratly or Paracel Islands.

India provided a $500 million line of credit to Vietnam for the acquisition of Indian defense systems during Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Hanoi in September 2016. There has been no information on exactly how that fund will be used, aside from $99 million allocated to produce an undisclosed number of patrol craft for Vietnam’s coast guard, including the license for Vietnam to begin local production. Vietnam may also move toward the acquisition of the BrahMos anti-ship missile (discussed below), though no agreement was reached during Indian Minister of Defense Manohar Parrikar’s visit to Hanoi in June 2016.

Vietnam is also trying to acquire niche capabilities to make up for shortfalls in its existing arsenal. One example is the Italian Pluto Plus mine-identification unmanned underwater vehicle, which was revealed in May 2016. It will assist Soviet 1960s Yurkaminesweepers currently, but at the very end of their service life, with the VPAN. This acquisition also shows the VPA’s penchant for integrating older Russian systems with new Western weapons and equipment, and for looking westward for new purchases when it needs to. That being said, the skeleton of the VPA’s armory remains Russian, now and at least in the near future. And attempts at integrating Western and Soviet/Russian platforms have historically not gone well.

In sum, Vietnam’s naval developments to date have been impressive. Between 2011 and 2015, naval vessels accounted for 44 percent of defense imports. We expect in the coming years for Vietnam to continue with this trajectory, though at a slower rate as the new focus will be on the ground force. Maritime acquisitions will continue, yet the navy remains a small service arm that is unlikely to grow significantly.

Air Force

Vietnam’s maritime power projection capabilities have not been matched in the air. With extremely costly platforms, Vietnam has lagged in training and maintenance. In 2016 alone, Vietnam suffered the losses of four aircraft (a Su-30MK2 multirole fighter, a CASA 212 patrol/transport turboprop, an L-39 training jet, and an EC-130 helicopter) from its small fleet, killing 13 personnel.

Between 1994-1996 Vietnam acquired a full regiment of Su-27s from Russia. Though it suffered only one loss, they are nearing the end of the airframe lifespans. There are reports that Vietnam is currently overhauling the fleet, both airframes and avionics, to extend their lifespan.

From 2003-2016, Vietnam acquired 36 Su-30s, or three regiments. At least three regiments, one each of Su-27s, Su-30s, and L-39s, are not complete due to crashes and maintenance issues.

Vietnam is currently deliberating the replacement for its large fleet of 1960s era MiG-21s (144) and even the Su-22s, although the latter are still in service. The per-unit cost of modern fourth generation fighters precludes a one-to-one replacement for these aircraft. Vietnam is currently exploring the purchase of the French Rafale and Swedish Gripen (also in the Thai inventory). Though there have been press reports that Vietnam is considering the U.S. F-16 as a possible contender, this is highly unlikely due to U.S. concerns over technology transfer to third parties, as well as Vietnam’s apprehension about purchasing second-hand equipment.

With the lifting of the U.S. arms embargo, further speculation fell on the Vietnamese acquisition of advanced maritime surveillance aircraft from the United States. The VPA sent a team to Hawaii in April 2016 to observe the P-3C in action. Though Vietnam enjoys some high level Congressional support for arms sales, it is unlikely that they will receive approval for new and advanced P-3s, having to settle instead for used aircraft from either the United States or, more likely, Japan. While there are suggestions that Japan, having failed in its bid to sell its Soryu-class submarines to Australia, is keen to enter the global arms market with its Kawasaki P1 maritime surveillance aircraft, it is simply too expensive for Vietnam.

Other than combat aircraft, in 2014, Vietnam also purchased DHC-6 maritime patrol planes from Canada as well as several Casa C-295 military cargo planes from EADS to replace its aging fleet of Soviet An-26s.

The VPAAF also has requirements for additional helicopters. While there are a couple of military helicopter transportation regiments, most of the newest helicopters are assigned to the Ministry of National Defense’s 18th Corps, or the Vietnam Helicopter Corporation. It is equipped with aircraft such as the AgustaWestland AW-189, Eurocopter Super Puma and EC-225, and Russian Mi-171. During peacetime, these are used for economic purposes such as VIP transportation or HADR missions. Should war come, the VPA has suggested that the 18th Corps will be converted into two attack helicopter regiments. This would greatly augment the VPAAF rotary wing force and its close air support capability.

In sum, while strides have been made and will be made in the near future, air force modernization is falling short compared to naval modernization. Between 2011-15, air acquisitions accounted for 37 percent of total imports, not far below the navy’s 44 percent, which has seen far more hardware brought on line. The costs of the platforms, training, and maintenance have made the high accident rates unsustainable.

Ground Forces

The VPA dominates Vietnam’s defense in manpower, though the size of the force has gradually been cut. It remains wedded to its long history and doctrine of people’s warfare. As such, it has lagged behind in modernization. However, General Vo Van Tuan, VPA vice chief of staff, recently announced that ground force modernization will be the next focus of defense modernization. Under the current defense law, the size of the VPA’s ground forces should be kept at or near the current level.

A main focus is the armored force. Vietnam has already purchased the KZKT-7428 heavy tank tractor from Russia in preparation for the arrival of a new main battle tank and recently the head of the Russian tank producer Uralvagonzavod revealedthat Hanoi is currently negotiating with them for the purchase of modern T-90MS tanks, with the final numbers of tanks and price not yet concluded. Yet, due to the price, Vietnam is unlikely to replace its huge corps of T-55 tanks on a one-to-one basis. As such it is aiming to upgrade its T-55 with a new fire control system and additional armor so as to be more capable in modern warfare.

Vietnam is also studying the French 155 mm CAESAR artillery system. A French website said that Nexter, the producer of CAESAR artillery system, revealed that Vietnam has ordered 18 such systems, of a total 108. This has not been verified. Acquiring a 155 mm-caliber system means moving away from the Soviet 152 mm system, and if the acquisition is true, it presents another challenge and strain for the VPA logistic branch.

The ground force also needs new Infantry Fighting Vehicles and Armored Personnel Carriers, as its arsenal mostly consists of the 1960-era BTR-60s and BMP-1s. However, it needs to compete with the Marine Corps for the funding for this upgrade, as the Marines are also relying heavily on outdated BMP-1s and PT-76s and also need new amphibious IFVs and APCs. It is possible that the ground force has to contend with updates for its vehicles, while the Marines are slated for new ones; the latter has been featured in state media recently, training for island recapture and amphibious landing using APCs and amphibious tanks, showing their importance.

Vietnam has made significant investments in modernizing its small arms for its ground forces. Vietnam has purchased the Galil assault rifle from Israel for general issue for its ground forces, while acquiring Tavor assault rifles, Negev machine guns, and Galatz sniper rifles for the Marine Corps. Vietnam has obtained a production license for the Galil family of weaponry and is now indigenously producing NATO ammunition (NATO 5.56×45) for them.

While the ground force remains the most favored and politically influential of the service arms, to date the Navy and the Air Force have seen far greater investment in their modernization due to their pertinence to the South China Sea dispute. The issue for ground force modernization is of course resources. The numbers of pieces of equipment in block modernization programs are enormous. Yet Vietnamese military planners remain concerned about Chinese PLA modernization and ability to make swift small-scale incursions, unlike their costly, large-scale 1978-79 invasion.

Missiles

While most of the attention in the western media has focused on Vietnam’s new maritime capabilities, it is actually their missile force that probably gives Chinese defense planners the greatest cause for alarm. Vietnam has recently negotiated on purchasing advanced hypersonic BrahMos cruise missiles from India/Russia, as well as submarine- and ship-launched Klub missiles to target Chinese facilities in the Spratlys and Paracels. China clearly has lobbied Russia to block the sale of the BrahMos missiles, but it appears that the deal is proceeding.

Vietnam is also in possession of Scud surface-to-surface ballistic missiles, which it imported from North Korea in the 1990s. These are currently based at Bien Hoa, and with a supposed range of 500 km, they can reach the whole of Cambodia and the westernmost Spratly islands. The chief of the artillery branch has said that in the near future, Vietnam will procure a new ballistic surface-to-surface missile, though there are other more pressing acquisitions.

Recently, SIPRI and Vietnamese state media revealed that Vietnam has acquired EXTRA and ACCULAR surface-to-surface guided rockets with extremely high accuracy, with 150 km and 40 km ranges, respectively. These are presumably based around Cam Ranh, but foreign reports have surfacedthat this equipment may have been moved to Vietnamese held features in the Spratlys. The accuracy of these reports have not been confirmed, and Vietnam has denied conducting such a move. Recently, there have been articles titled “The duty of EXTRA system in protecting the sea and islands” on the Vietnamese media; yet, even with a range of 150 km and based at Cam Ranh, these systems cannot reach any disputed islands, while being stationed at Spratlys will help Vietnam threaten any Chinese installation nearby. The system adds another layer to Vietnam’s coastal defenses.

Currently, Vietnam is fielding three coastal defense missile units: one in Hai Phong, equipped with the Redut system with a range of 460 km (to counter any Chinese efforts to blockade the Gulf of Tonkin using the Hainan Island bases); one in Da Nang, with the Rubezh system and 80 km range; and the most modern one in Ninh Thuan, just south of Cam Ranh, with the Russian-built Bastion-P system and a 300 km range. A fourth unit is being built at Phu Yen, north of Cam Ranh; it is very probable that this regiment will also be equipped with the Bastion-P system, or maybe even a BrahMos system. The new regiment will cover the last unprotected coastal stretch of Central Vietnam, as well as providing additional protection for Cam Ranh Bay, where the most costly and modern VPAN assets are based.

Vietnam has also acquired a new short-medium range air defense battery from Israel, the SPYDER system. These serve to augment the long range S-300 and the older short-range S-125 and Strela-10 systems that Vietnam currently fields. The SPYDER are positioned close to Hanoi, providing another layer of air defense for the capital. At present, Vietnam has only acquired one regiment from Israel, but news articles say that they want at least four regiments to be deployed across the country. This is a major acquisition from Israel, a country with whom Vietnam hopes to increase defense cooperation.

ISR

Despite the rapid acquisition of kinetic assets, Vietnam’s ISR (intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) capabilities are relatively poor. It has repeatedly been surprised by Chinese operations in the South China Sea.

Vietnam recently acquired the Coast Watcher 100 Long Range Coastal Surveillance Radar from France, which provides over the horizon surveillance of up to 170 km and can detect approaching ships in all weather. It can also detect low-flying threats such as helicopters. This system is positioned in the Spratlys, where it allows Vietnam to have a full surveillance and detection in the islands.

Vietnamese media revealed that Vietnam has purchased a Japanese ASNARO-2 Earth Observation Satellite. It is capable of taking high resolution pictures at night and in cloudy conditions, and can be used for military purposes. The results from this satellite, coupled with access to an Indian satellite following a 2016 agreement to place a satellite tracking and imaging center in Vietnam, will offer the VPA unprecedented tracking capability in the South China Sea. It is expected that ASNARO-2 will be launched in 2017.

VietTel, the VPA-owned telecommunication company, already produces warning radars to support anti-air missile batteries and recently developed a new C4ISR system for the VPA. It has developed several small UAVs and is aiming to manufacture a high-altitude long-endurance drone with Belorussian cooperation. The UAV HS-6L, unveiled in December 2015, has an endurance of 35 hours and a range of 4,000 km and will greatly increase Vietnam ISR capability over the South China Sea. Vietnam is also leasing a Heron long-endurance UAV from Israel, and is clearly seeking to gain technology transfer. These will further support Vietnam’s effort to track new development in the South China Sea.

Conclusion

Vietnam undoubtedly has made great strides in its military and defense capability, yet it remains to be seen how they will absorb these new systems and link them all together in a credible and effective modern doctrine. Training, especially on incorporating and operating new weapon systems, also needs to be improved. Nevertheless, the large investment over the past couple of decades has given the VPA great potential. How defense planners harness these capabilities and fulfill that potential remains an open question. The forthcoming defense white paper should present crucial details on how the VPA views its roles and responsibilities.

For the near future, we can expect to see more new weaponry and equipment, such as armored vehicles and artillery systems, be purchased and developed for ground forces. However, modernization for the Navy and the Air Force will not slow down much: new surface ships are being negotiated and self-produced, and a new lightweight fighter jet will be chosen. Maritime and aerial capabilities will continue to be augmented, as well as ISR, due to urgent needs in the South China Sea.

But in the final analysis, we still do not know what Vietnam’s current defense strategy is, beyond fielding a minimal credible deterrent. At present the current strategy seems to be simply to sow seeds of concern in the eyes of Chinese military planners. But with the asymmetry in Chinese defense spending, that approach might not be sustainable.

Zachary Abuza, PhD, is a Professor at the National War College where he specializes in Southeast Asian security issues. The views expressed here are his own, and not the views of the Department of Defense or National War College. Follow him on Twitter @ZachAbuza.

Nguyen Nhat Anh is a graduate of the University of Texas at Dallas, where he focused on International Political Economy. You can follow him on Twitter @anhnnguyen93.

Wednesday, October 26, 2016

A poet with M.S died at the age of 50, by Anita Gates in the NYT 10/25/2016

Tuesday, October 25, 2016

An African-American writer won the 2016 Booker Prize, as reported by Alexandra Alter in the NYT 10/26/2016

Consciousness and the starting point of Inquiry: David Chalmers and his critic John Searle. Another project for investigation

Consciousness and the Philosophers’: An Exchange

In response to:

Consciousness & the Philosophers from the March 6, 1997 issue

To the Editors:

In my book The Conscious Mind, I deny a number of claims that John Searle finds “obvious,” and I make some claims that he finds “absurd” [NYR, March 6]. But if the mind-body problem has taught us anything, it is that nothing about consciousness is obvious, and that one person’s obvious truth is another person’s absurdity. So instead of throwing around this sort of language, it is best to examine the claims themselves and the arguments that I give for them, to see whether Searle says anything of substance that touches them.

The first is my claim that consciousness is a nonphysical feature of the world. I resisted this claim for a long time, before concluding that it is forced on one by a sound argument. The argument is complex, but the basic idea is simple: the physical structure of the world—the exact distribution of particles, fields, and forces in spacetime—is logically consistent with the absence of consciousness, so the presence of consciousness is a further fact about our world. Searle says this argument is “invalid”: he suggests that the physical structure of the world is equally consistent with the addition of flying pigs, but that it does not follow that flying is nonphysical.

Here Searle makes two elementary mistakes. First, he gets the form of the argument wrong. To show that flying is nonphysical, we would need to show that the world’s physical structure is consistent with the absence of flying. From the fact that one can add flying pigs to the world, nothing follows. Second, the scenario he describes is not consistent. A world with flying pigs would have a lot of extra matter hovering meters above the earth, for example, so it could not possibly have the same physical structure as ours. Putting these points together: the idea of a world physically identical to ours but without flying, or without pigs, or without rocks, is self-contradictory. But there is no contradiction in the idea of a world physically identical to ours without consciousness, as Searle himself admits.

The underlying point is that the position of pigs—and almost everything else about the world—is logically derivable from the world’s physical structure, but the presence of consciousness is not. So to explain why and how brains support consciousness, an account of the brain alone is not enough; to bridge the gap, one needs to add independent “bridging” laws. One can resist this conclusion only by adopting a hard-line deflationism about consciousness. That path has its own problems, but in any case it is not open to Searle, who holds that consciousness is irreducible. Irreducibility has its consequences. Consistency requires that one face them directly.

The next issue is my nonreductive functionalism. This bridging law claims that systems with the same functional organization have the same sort of conscious experiences. My detailed argument for this claim is not recognizable in the trivial argument that Searle presents as mine and rebuts. The basic idea, presented in Chapter Seven of the book but ignored by Searle, is that if the claim is false, then there can be massive changes in conscious experience which a subject can never notice. (Searle’s own position is rebutted on p. 258.) He also points to patients with Guillain-Barre syndrome as a counterexample to my claim, but this once again gets the logic wrong. My claim concerns functionally identical beings, so it is irrelevant to point to people who function differently. I certainly do not claim that beings whose functioning differs from ours are unconscious.

The final issue is panpsychism: the claim that some degree of consciousness is associated with every system in the natural world. Here Searle misstates my view: he says that I am “explicitly committed” to this position, when I merely explore it and remain agnostic; and he says incorrectly that it is an implication of property dualism and nonreductive functionalism. One can quite consistently embrace those views and reject panpsychism, so the latter could not possibly function as a “reductio ad absurdum” of the former. I note also that the view which I describe as “strangely beautiful,” and which Searle describes as “strangely self-indulgent,” is a view I reject.

I do argue that panpsychism is not as unreasonable as is often supposed, and that there is no knockdown argument against it. Searle helps confirm the latter claim: while protesting “absurdity,” his arguments against panpsychism have no substance. He declares that to be conscious, a system must have the right “causal powers,” which turn out to be the powers to produce consciousness: true, but trivial and entirely unhelpful. And he says that simple systems (such as thermostats) do not have the “structure” required for consciousness; but this is precisely the claim at issue, and he provides no argument to support it (if we knew what sort of structure were required for consciousness, the mind-body problem would be half-solved). So we are left where we started. Panpsychism remains counterintuitive, but it cannot be ruled out at the start of inquiry.

In place of substantive arguments, Searle provides gut reactions: every time he disagrees with a view I discuss, he calls it “absurd.” In the case of panpsychism (a view not endorsed by me), many might agree. In other cases, the word is devalued: it is not even surprising, for example, that mental terms such as “perception” are ambiguous between a process and a subjective experience; and given that a trillion interacting neurons can result in consciousness, there is no special absurdity in the idea that a trillion interacting silicon chips or humans might do the same. I do bite one bullet, in accepting that brain-based explanations of behavior can be given that do not invoke or imply consciousness (although this is not to say that consciousness is causally irrelevant). But Searle’s own view on irreducibility would commit him to this view too, if he could only draw the implication.

Once we factor out mistakes, misrepresentations, and gut feelings, we are left with not much more than Searle’s all-purpose critique: “the brain causes consciousness.” Although this mantra (repeated at least ten times) is apparently intended as a source of great wisdom, it settles almost nothing that is at issue. It is entirely compatible with all of my views: we just need to distinguish cause from effect, and to note that it does not imply that only the brain causes consciousness. Indeed, Searle’s claim is simply a statement of the problem, not a solution. If one accepts it, the real questions are: Why does the brain cause consciousness? In virtue of which of its properties? What are the relevant causal laws? Searle has nothing to say about these questions. A real answer requires a theory: not just a theory of the brain, but also a detailed theory of the laws that bridge brain and consciousness. Without fulfilling this project, on which I make a start in my book, our understanding of consciousness will always remain at a primitive level.

(Further remarks and a further reply to Searle are at http://ling.ucsc.edu/~chalmers/nyrb/.)

David Chalmers

University of California, Santa Cruz

John Searle replies: replies:

I am grateful that David Chalmers has replied to my review of his book, and I will try to answer every substantive point he makes. In my review, I pointed out that his combination of property dualism and functionalism led him to some “implausible” consequences. I did not claim, as he thinks, that these consequences are logically implied by his joint acceptance of property dualism and functionalism; rather I said that when he worked out the details of his position these views emerged. Property dualism is the view that there are two metaphysically distinct kinds of properties in the world, mental and physical. Functionalism is the view that the mental states of a “system,” whether human, machine, or otherwise, consist in physical functional states of that system; and functional states are defined in terms of sets of causal relations.

Here are four of his claims that I found unacceptable:

1.Chalmers thinks each of the psychological words, “pain,” “belief,” etc., has two completely independent meanings, one where it refers to nonconscious functional processes, and one where it refers to states of consciousness.

2.Consciousness is explanatorily irrelevant to anything physical that happens in the world. If you think you are reading this because you consciously want to read it, Chalmers says you are mistaken. Physical events can have only physical explanations, so consciousness plays no explanatory role whatever in your behavior or anyone else’s.

3.Even your own claims about your own consciousness are not explained by consciousness. If you say “I am in pain,” when you are in pain, it cannot be because you are in pain that you said it.

4.Consciousness is everywhere. Everything in the universe is conscious.

This view is called “panpsychism,” and is the view that I characterized as “absurd.”

Now, what has Chalmers to say about these points in his reply? He says that my opposition to these views is just a “gut reaction” without argument. Well, I tried to make my arguments clear, and in any case for views as implausible as these I believe the onus of proof is on him. But just to make my position as clear as possible let me state my arguments precisely:

1.As a native speaker of English, I know what these words mean, and there is no meaning of the word “pain,” for example, where for every conscious pain in the world there must be a correlated nonconscious functional state which is also called “pain.” On the standard dictionary definition, “pain” means unpleasant sensation, and that definition agrees with my usage as well as that of my fellow English speakers. He thinks otherwise. The onus is surely on him to prove his claim.

2.If we know anything about how human psychology works, we know that conscious desires, inclinations, preferences, etc., affect human behavior. I frequently drink, for example, because I am thirsty. If you get a philosophical result that is inconsistent with this fact, as he does, you had better go back and examine your premises. Of course, it is conceivable that science might show that we are mistaken about this, but to do so would require a major scientific revolution and such a revolution could not be established by the armchair theorizing in which he engages.

3.In my own case, when I am in pain, I sometimes say “I am in pain,” precisely because I am in pain. I experience all three: the pain, my reporting the pain, and my reporting it for the reason that I have it. These are just facts about my own experiences. I take it other people’s experiences are not all that different from mine. What sort of arguments does he want in addition to these plain facts? Once again, if you get a result that denies this, then you had better go back and look at your premises. His conclusions are best understood not as the wonderful discoveries he thinks; rather each is a reductio ad absurdum of his premises.

4.What about panpsychism, his view that consciousness is in rocks, thermostats, and electrons (his examples), indeed everywhere? I am not sure what he expects as an argument against this view. The only thing one can say is that we know too much about how the world works to take this view seriously as a scientific hypothesis. Does he want me to tell him what we know? Perhaps he does.

We know that human and some animal brains are conscious. Those living systems with certain sorts of nervous systems are the only systems in the world that we know for a fact are conscious. We also know that consciousness in these systems is caused by quite specific neurobiological processes. We do not know the details of how the brain does it, but we know, for example, that if you interfere with the processes in certain ways—general anesthetic, or a blow to the head, for example—the patient becomes unconscious and if you get some of the brain processes going again the patient regains consciousness. The processes are causal processes. They cause consciousness. Now, for someone seriously interested in how the world actually works, thermostats, rocks, and electrons are not even candidates to have anything remotely like these processes, or to have any processes capable of having equivalent causal powers to the specific features of neurobiology. Of course as a science fiction fantasy we can imagine conscious thermostats, but science fiction is not science. And it is not philosophy either.

The most astonishing thing in Chalmers’s letter is the claim that he did not “endorse” panpsychism, that he is “agnostic” about it. Well, in his book he presents extensive arguments for it and defenses of it. Here is what he actually says. First, he tells us that “consciousness arises from functional organization” (p. 249). And what is it about functional organization that does the job? It is, he tells us, “information” in his special sense of that word according to which everything in the world has information in it. “We might put this by suggesting as a basic principle that information (in the actual world) has two aspects, a physical and a phenomenal aspect” (p. 286). The closest he gets to agnosticism is this: “I do not have any knockdown arguments to prove that information is the key to the link between physical processes and conscious experience,” but he immediately adds, “but there are some indirect ways of giving support to the idea.” Whereupon he gives us several arguments for the double aspect principle (p. 287). He hasn’t proven panpsychism, but it is a hypothesis he thinks is well supported. Since information in his sense is everywhere then consciousness is everywhere. Taken together his premises imply panpsychism. If he argues that functional organization gives rise to consciousness, that it does so in virtue of information, that anything that has information would be conscious and that everything has information, then he is arguing for the view that everything is conscious, by any logic that I am aware of.

And if he is not supporting panpsychism, then why does he devote an entire section of a chapter to “What is it like to be a thermostat?” in which he describes the conscious life of thermostats?

At least part of the section is worth quoting in full:

Certainly it will not be very interesting to be a thermostat. The information processing is so simple that we should expect the corresponding phenomenal states to be equally simple. There will be three primitively different phenomenal states, with no further structure. Perhaps we can think of these states by analogy to our experiences of black, white, and gray: a thermostat can have an all-black phenomenal field, an all-white field, or an all-gray field. But even this is to impute far too much structure to the thermostat’s experiences, by suggesting the dimensionality of a visual field and the relatively rich natures of black, white, and gray. We should really expect something much simpler, for which there is no analog in our experience. We will likely be unable to sympathetically imagine these experiences any better than a blind person can imagine sight, or than a human can imagine what it is like to be a bat; but we can at least intellectually know something about their basic structure.

He then goes on to try to make the conscious life of thermostats more plausible by comparing our inability to appreciate thermostats with our difficulty in understanding the consciousness of animals. And two pages later he adds,

But thermostats are really no different from brains here.

What are we to make of his analogy between the consciousness of animals and the consciousness of thermostats? I do not believe that anyone who writes such prose can be serious about the results of neurobiology. In any case they do not exhibit an attitude that is “agnostic” about whether thermostats are conscious. And, according to him, if thermostats are conscious then everything is.

Chalmers genuinely was agnostic about the view that the whole universe consists of little bits of consciousness. He put this forward as a “strangely beautiful” possibility to be taken seriously. Now he tells us it is a view he “rejects.” He did not reject it in his book.

The general strategy of Chalmers’s book is to present his several basic premises, most importantly, property dualism and functionalism, and then draw the consequences I have described. When he gets such absurd consequences, he thinks they must be true because they follow from the premises. I am suggesting that his conclusions cast doubt on the premises, which are in any case, insufficiently established. So, let’s go back and look at his argument for two of his most important premises, “property dualism” and “nonreductive functionalism,” the two he mentions in his letter.

In his argument for property dualism, he says, correctly, that you can imagine a world that has the same physical features that our world has—but minus consciousness. Quite so, but in order to imagine such a world, you have to imagine a change in the laws of nature, a change in those laws by which physics and biology cause and realize consciousness. But then, I argued, if you are allowed to mess around with the laws of nature, you can make the same point about flying pigs. If I am allowed to imagine a change in the laws of nature, then I can imagine the laws of nature changed so pigs can fly. He points out, again correctly, that that would involve a change in the distribution of physical features, because now pigs would be up in the air. But my answer to that, which I apparently failed to make clear, is that if consciousness is a physical feature of brains, then the absence of consciousness is also a change in the physical features of the world. That is, his argument works to establish property dualism only if it assumes that consciousness is not a physical feature, but that is what the argument was supposed to prove. From the facts of nature, including the laws, you can derive logically that this brain must be conscious. From the facts of nature, including the laws, you can derive that this pig can’t fly. The two cases are parallel. The real difference is that consciousness is irreducible. But irreducibility by itself is not a proof of property dualism.

Now I turn to his argument for “non-reductive functionalism.” The argument is that systems with the same nonconscious functional organization must have the same sort of conscious experiences. But the argument that he gives for this in his book and repeats in his reply, begs the question. Here is how he summarizes it:

If there were not a perfect match between conscious experiences and functional organization, then there could be massive changes in someone’s conscious experiences, which the subject having those experiences would never notice. But in this last statement, the word “notice” is not used in the conscious sense of “notice.” It refers to the noticing behavior of a nonconscious functional organization. Remember for Chalmers all these words have two meanings, one implying consciousness, one nonconscious functional organization. Thus, the argument begs the question by assuming that radical changes in a person’s consciousness, including his conscious noticing, must be matched by changes in the nonconscious functional organization that produces noticing behavior. But that is precisely the point at issue. What the argument has to show, if it is going to work, is that there must be a perfect match between an agent’s inner experiences and his external behavior together with the “functional organization” of which the behavior is a part. But he gives no argument for this. The only argument is the question-begging: there must be such a match because otherwise there wouldn’t be a match between the external noticing part of the match and the internal experience. He says incorrectly that the Guillain-Barre patients who have consciousness but the wrong functional organization are irrelevant, because they “function differently.” But differently from what? As far as their physical behavior is concerned they function exactly like people who are totally unconscious, and thus on his definition they have exactly the same “functional organization” as unconscious people, even though they are perfectly conscious. Remember “functional organization” for him is always nonconscious. The Guillain-Barre patients have the same functional organization, but different consciousness. Therefore there is no perfect match between functional organization and consciousness. Q.E.D.

Chalmers resents the fact that I frequently try to remind him that brains cause consciousness, a claim he calls a “mantra.” But I don’t think he has fully appreciated its significance. Consciousness is above all a biological phenomenon, like digestion or photosynthesis. This is just a fact of nature that has to be respected by any philosophical account. Of course, in principle we might build a conscious machine out of nonbiological materials. If we can build an artificial heart that pumps blood, why not an artificial brain that causes consciousness? But the essential step in the project of understanding consciousness and creating it artificially is to figure out in detail how the brain does it as a specific biological process in real life. Initially, at least, the answer will have to be given in terms like “synapse,” “peptides,” “ion channels,” “40 Hertz,” “neuronal maps,” etc., because those are real features of the real mechanism we are studying. Later on we might discover more general principles that permit us to abstract away from the biology.

But, and this is the point, Chalmers’s candidates for explaining consciousness, “functional organization” and “information,” are nonstarters, because as he uses them, they have no causal explanatory power. To the extent that you make the function and the information specific, they exist only relative to observers and interpreters. Something is a thermostat only to someone who can interpret it or use it as such. The tree rings are information about the age of the tree only to someone capable of interpreting them. If you strip away the observers and interpreters then the notions become empty, because now everything has information in it and has some sort of “functional organization” or other. The problem is not just that Chalmers fails to give us any reason to suppose that the specific mechanisms by which brains cause consciousness could be explained by “functional organization” and “information,” rather he couldn’t. As he uses them, these are empty buzzwords. For all its ingenuity I am afraid his book is really no help in the project of understanding how the brain causes consciousness.